The coronavirus pandemic cleared out the offices and moved many of us to our home offices. As a result, both designers – myself included – and teams had to adjust their working methods. One crucial challenge I had to tackle was how user-centric design could be done remotely. What tools to utilise and how? I’ve reflected on my experiences during the exceptional times and will share what I’ve learned in the process. I have put together various tips for conducting user research and creating user-centred design remotely.

“UX without users is not UX”

A successful product or service cannot be created without involving users in the design process. User research is a key part of good design, and it allows designers and developers to understand users’ challenges and make their everyday lives easier by removing friction and creating value. Engaging users reduce the risk of failure and also contributes to achieving business goals.

Understanding users and receiving feedback throughout the process helps ensure that we’re on the right track. Even the most well-founded concept or user interface is nothing more than a good guess before its functionality has been validated with real users.

User-centric design methods include:

- Interviews: Individual users are interviewed more deeply on a specific topic, such as the motives for using a service or a product

- User test: The user is asked to perform a set of tasks by using either a prototype or a finished product/service.

- Ethnographic field study: The user is observed in a real context and environment.

- Card sorting: The user is asked to organise parts of, for example, a service into groups and entities.

Qualitative user research is usually conducted in the same physical space as the users. A team spread across different countries or an international target group can make an exception to this. However, the new ways of working have opened new opportunities and alternative ways of doing things. So, what is it like to conduct user research remotely?

Photo: A user test at Fraktio’s office. The facilitator is in a separate room dedicated to user testing with the user while the rest of the team observes the situation via video and takes notes.

The benefits of remote user research

User interviews and tests are relatively quick and affordable to arrange remotely. As there’s no need to travel to a physical location or to book separate rooms, it’s easier to squeeze the meetings into calendars. In addition, there’ll be hardly any lost working time or additional costs due to travel.

Remote research is a great opportunity for geographical decentralisation. In my project, for example, the client’s mobile application has users all across Finland. Under normal circumstances, not all of them would’ve been able to come to our Helsinki office for a meeting, but we were now able to get input from users from Helsinki, Seinäjoki and Kuopio – all in different parts of the country. This helped us understand the users’ different starting points for using the application and the service, among other things.

What particularly stuck with me was how one of the users I talked to was dressed in their work clothes and took part in the interview from their own car outside the work site after their working day. Hearing the thoughts and experiences of a HVAC entrepreneur whose work is busy and mobile, was particularly valuable to our project.

The downsides of remote user research

User research conducted remotely also has its challenges. For example, an ethnographic field study can’t really be done remotely as it requires being in the same space as the user.

It’s a good idea to reserve more time than usual for remote user testing since technical problems are always present in both software and hardware. Applications may have unexpected problems, and a poor Internet connection may cause audio and video connections to break up. Also, not everyone has the needed devices (e.g. computer + webcam), which can make recruiting users difficult. The introduction of new tools, such as a video call application or a prototype, may also pose challenges as not all people are as tech-savvy as others.

Still, perhaps the biggest drawback has to do with interaction with the users. An unstable Internet connection may cause people to accidentally talk over each other, which will affect the flow of the meeting. It’s also difficult, if not impossible, to interpret body language and gestures correctly via video. It can also be more difficult to read the room: when is the right time to ask a follow-up question or to help the user with a problem? What does silence mean? Is there something else catching the user’s attention that is not visible on the video or screen sharing?

Since users can attend a remote test from home or their office, it can be easier to recruit users as taking part in the test will be more convenient for them. But perhaps the bar for last minute cancellations will also be lower if something more important comes up?

Recommended tools for remote design work

It’s quite easy to arrange user interviews and tests remotely on a video call. However, when recruiting users, it’s a good idea to make sure that they have the necessary devices at their disposal. Many video call apps have recording functionality, which allows the facilitator to be fully present rather than trying to write down notes at the same time. The recording can also be shared with the rest of the team afterwards. Remember to always ask the user for their permission before starting the recording.

Tools such as Google Meet, Zoom, Whereby and Teams are well suited for video calls. The main thing is the possibility to record the video call. You should also try to minimise any technical hassle where possible. It would be best if the user attending the meeting didn’t need to install new apps or browser plugins.

For card sorting, you can use a video call in combination with Mural or Miro. These tools are like virtual post-it boards that can also be used in different kinds of remote workshops. We have successfully used Mural in both Design Sprints and retrospectives.

In user testing, the user usually performs tasks using a prototype. In the case of online services or websites, the remote test won’t cause much trouble as the user can open, for example, a Figma or an InVision prototype in the browser on their computer and share it on the video call.

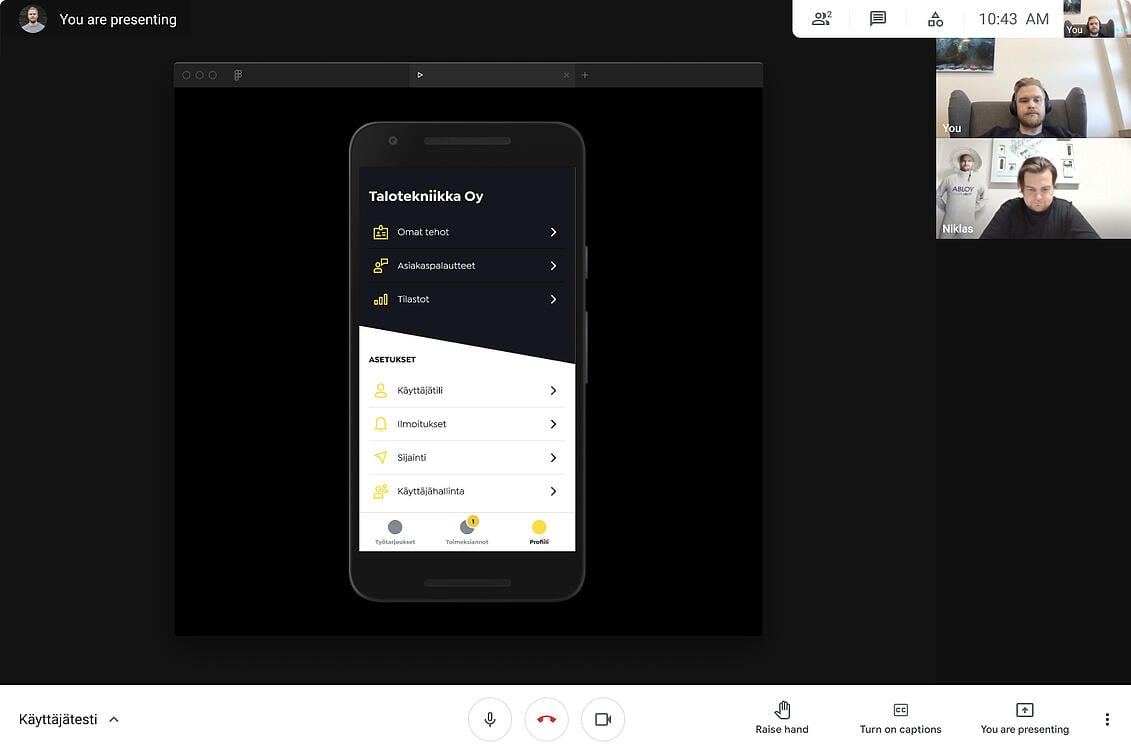

Photo: A remote user test for a mobile app in progress

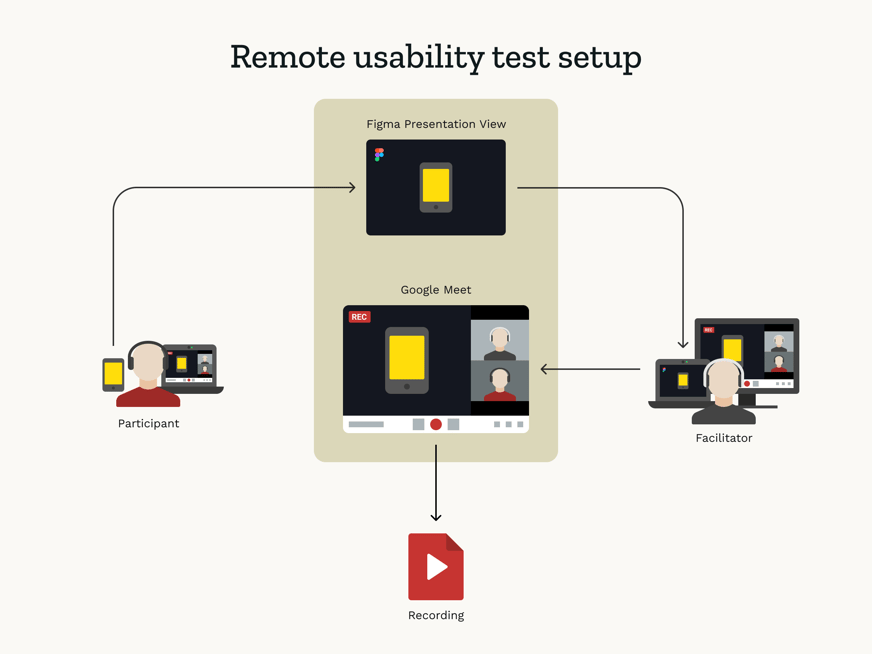

When testing mobile apps, the situation is a bit more complex if the goal is for the user to open the prototype on their phone and for the experience to match the use of a real mobile app. Many design and prototyping tools offer their own mobile application, through which the prototype viewing experience better reflects reality. But how can you share the prototype on a video call?

There are at least two options:

- The user can also install a video app such as Google Meet on their phone and join a video call on both their computer (audio + video) and phone (prototype/screen sharing).

- The user can open a Figma prototype in their phone’s Internet browser, and the facilitator can monitor the user’s movements in the prototype in real time on their computer in Figma’s Presentation View. The facilitator can then share this from their own screen on the video call so that the audio, video and the user's movements in the prototype can all be recorded.

The perfect remote user test arrangement?

I wanted to make the test experience as effortless as possible for the users (and for myself, of course): all they had to do was show up instead of creating accounts, installing apps and unnecessary hassle. I tested the arrangement with a couple of colleagues, and everything seemed to be in order.

In the first test, the plan worked like a charm. I had instructed the users in advance, so they were prepared and knew what to expect. The audio and video worked well, as did the sharing of the prototype. But then, right at the end of the half-hour, my computer froze completely: the battery had drained out completely even though it was plugged into the charger. Apparently, Figma’s Presentation View combined with Google Meet and the recordings was too much.

The next test session was half an hour away, so I had enough time to bring my computer back to life by then. Still, I decided to minimise the risks and ask the users in the next group to open the prototype in their computer’s browser instead of on the phone, even if the experience wouldn’t be completely realistic that way. I considered it to be a lesser evil (given the main functionalities being tested) than asking the users to install Google Meet on their phones.

In the following tests, problems were also caused by an unexpected loss of audio, which forced us to switch to the Whereby video chat application on the fly. Because of that, I couldn’t get everything recorded and had to take notes at the same time. Fortunately, the tests went quite well despite all the problems, even though the arrangement was no longer optimal.

Lessons learned and tips

I’ve been facilitating or arranging several remote user research sessions in the past couple of years. Here are the most important lessons I’ve learned from my journey:

- “Just do it.” Don’t use circumstances as an excuse for skipping user research. It is important not to accumulate “usability backlog” by postponing user research into the future. Do it now.

- Recruit more users than necessary. Remote participation may be easier to cancel at the last minute.

- Test the functioning of the tools and devices with a colleague. Go through the entire test once or twice.

- Make the experience as easy as possible for the users. Your target group and users may not be tech-savvy. They might be busy. Try to minimise the need for creating accounts or installing apps for the meeting. Give clear and comprehensive instructions to the users in advance.

- Arrange a quiet and distraction-free space for yourself. Turn off Slack, mute your phone and close unnecessary browser tabs. Instruct the users in advance to do the same.

- Reserve extra time. If you can have two on-site user tests in an hour, you should reserve at least 15 minutes of extra time for remote tests. Also, leave another 15 minutes of buffer time between the meetings. It may be “easier” to be late for a remote session due to technical hassle or a drawn-out previous meeting, for example. Similarly, various technical issues may slow down the progress of the session.

- Make a plan B in case there’s a problem. Plan in advance what you will do if you suddenly lose the audio. How can you communicate with the user if you come across problems? What tools can you switch to on the fly?

- Ask a backup facilitator to join. It’s a good idea to keep another person on standby to write notes if there are problems with recording the video call.

Will remote user research become the norm?

The popularity of remote work is here to stay. How has this affected the work of a designer?

Many designers and organisations have been gaining experience of remote user tests or interviews in the past year, if not before, which has expanded their toolboxes. Remote research will continue to be a useful way to carry on user tests in the future, especially given its added benefits of being relatively quick to set up as well as affordable.

The pandemic opened up even more new international job opportunities for designers as entire companies are now operating remotely. In addition, existing tools will continue to be improved and new ones will be created to make it easier for designers to work completely remotely. I, for one, hope that Figma is going to make improvements to the performance of Presentation View 🙂

However, I don’t believe that remote user research will replace on-site research entirely because technology can never fully replace the humane side of the job. It’s easier for the facilitator to interpret the user’s body language, read the room in general and be present when they are in the same physical space. This is particularly important in the case of more challenging projects and when developing new ways of interaction between a person and a device.

Interested in learning more about user-centered design?

Check out our training programmes in which you can learn about service design and Design Sprint methods, among other things.